Emporia Main Street recently conducted a survey on behalf of a local alternative transportation group. I’m sure they will reference the results of the survey as they move forward with their future projects, but a brief overview of some survey responses (the responses were anonymous, so we don’t know who said what) revealed some interesting trends. Several factions (drivers, bikers and pedestrians) noted an entitled sense to road ownership. Drivers often pointed out that it was “hard to see” or “we’re bigger and others need to understand that”. Some bicyclists noted the health benefits and tourism impact of a bicycle culture. Many pedestrians cited their inherent right to feel safe as they walked or ran along their chosen path. So, who is correct?

Everyone is correct! The road belongs to cars, trucks, motorcycles, bicycles, pedestrians and more. All users have rights to the road and responsibilities on the road. Now, we could end the article right there, but this is Main Street and we like to take a historical look on the evolution of how we got to this transportation juncture and what the newest studies tell us about traffic interaction to add context to a discussion.

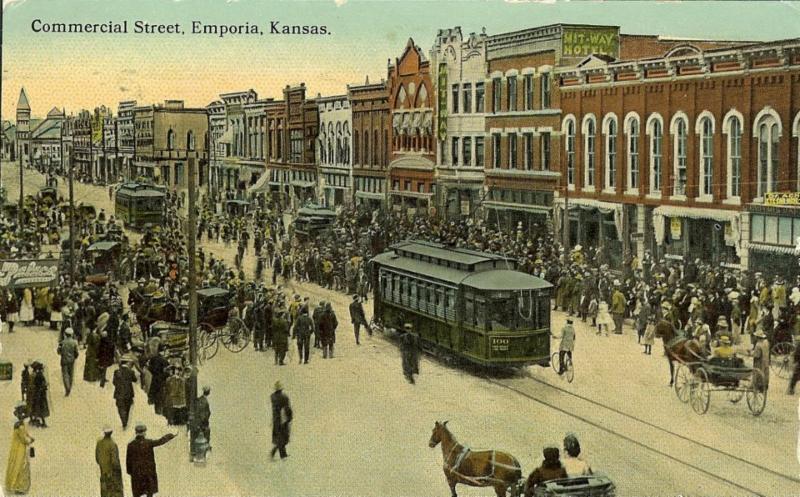

Most roads in the area predate mechanized vehicles. Older pictures of downtown Emporia show horses, buggies, trolleys and pedestrians together en masse as they moved about their daily lives in a dense urban environment. The Roman Empire’s dominance was based, in part, on roads. Horses and pedestrians were part of road traffic almost from the inception of the road concept, and wheeled vehicles soon followed. The first verifiable modern bicycle in the United States was patented in 1818, with what most people would recognize as a “modern” design arriving in the 1880’s. The first modern internal combustion engine car was patented in 1879, and the first running gasoline powered car was built in the United States in 1893. Though, the first mass production of cars didn’t start until Oldsmobile started imparting the factory process on vehicle production in Lansing, Michigan in 1902.

The advent of self-propelled vehicles introduced into an environment dominated by pedestrians, horses and horse drawn carriages was fairly chaotic. When automobiles were introduced into community cores, significant speed restrictions were often imposed (under ten miles per hour), and cars were expected to navigate an area swarming with people and animals. On the rare occasion that a driver hit a pedestrian and killed them, it generally wasn’t labeled an accident, and drivers were subject to manslaughter charges (if an angry mob didn’t get to them first.) So, what changed? How did we change from the swell of humanity in a central business district to an ordered and auto-centric style of transportation we see today?

In the roaring 20’s, “auto clubs” sprang up throughout the United States to promote the concept of driving. The technology present in cars of the time allowed them to travel much faster than an imposed ten mile an hour speed limit, and clubs lobbied for faster speeds and a change from automatic vehicular responsibility in an accident scenario to pedestrian responsibility. Some auto club members became part of public safety councils. It was during this time that the concept of jaywalking was introduced. Car companies like Packard went so far as to create fake tombstones on sidewalks that highlighted the irresponsible nature of the pedestrian “stepping into the street without looking.”

As technology in personal conveyance improved, and industrialists associated with the automotive industry gathered significant resources, internal public transit systems were altered. At one time, communities like Emporia had a system of electrically controlled trolleys. Set trolley systems located in the center of streets often prevented the unfettered flow of vehicular traffic. Across twenty five major metropolitan areas in the United States, the public transit systems were evolved from set trolleys to buses via shell companies. The resulting fallout is sometimes referred to as The Great American Street Car Scandal. Once set rail based transportation systems were removed from community cores, the modern auto based core transit system was born.

The usage of the road has changed dramatically over the past century. As communities pursued policies of separation through processes like zoning, travel times expanded and people lived further away from jobs, entertainment and other amenities that once were the basis of community interaction. The same “separate” philosophy has been extended to modes of transportation. Roads are dominated by cars. Bike trails are for bikes. Running paths are for walkers/runners. But does a separatist system actually work?

When we look at studies cited in newer literature like Tactical Urbanism, Happy City, and Walkable City, we see that separating systems doesn’t fix the root of the problem. The root problem is a combination of awareness, speed and respect. Regardless of your mode of transportation, you need to be aware of your surroundings and interact with them defensively. Assume that you will encounter multiple types of conveyance at any given time. Travel at speeds that allow you to comfortably avoid others within a transportation system. Respect the fact that roads are owned by everyone. Everyone has the right, unless otherwise legally specified, to utilize a road as part of their transportation network. It doesn’t matter if you are a pedestrian, bike rider or in a traditional vehicle; we all have rights and responsibilities as we move through a community.

Newer traffic studies indicate something that is counter intuitive to separatist transportation thinking: putting multiple types of transportation together in the same environment frequently actually makes all types of travel safer. As bike riding, running and other forms of transportation become more common to drivers that interact with these alternate forms of transportation, they have a better understanding of how to interact. Separating forms of transportation makes interaction less frequent, and individuals don’t always respond well to something “new” on the road.

We are entering a very busy period for Emporia. Over the next few months you will see bike travel and pedestrian traffic increase significantly all over town. With the epidemics of obesity, heart disease and diabetes in this country, we should be ecstatic that people are taking the initiative to get healthy through exercise. With our need to function as a community with engaged citizens, we should be proud of people that get outside their own four walls to interact with their city. So, lets remember this year to get out and explore your community in different ways. Get healthy. Get some fresh air, and respect everyone regardless of the way they chose to use the road while respecting the rules of the road meant to keep us safe.

Check out this article and MUCH more in this week’s Emporia Main Street E-newsletter!